The related topic “Metadata by Hand” is an introduction to writing your own metadata in JavaScript rather than depending on the server to generate it for you. It tell you all you need to know about writing metadata for your model.

This topic goes deeper into the details. It covers more of the options. It explains in greater depth what is going on and the relationship between the Breeze Labs MetadataHelper and the native Breeze metadata format.

The code shown in this topic is adapted from metadataOnClient.js in the Breeze “DocCode” sample. Try that sample to explore Breeze in general and metadata in particular through the medium of QUnit tests.

The Breeze client needs metadata to make entity data work for you: to compose queries, identify objects by key, navigate to related entities, track changed state, raise property-changed events, validate data entry, and serialize entities to the server or local storage.

Whenever you query the server, Breeze uses metadata to identify entity data in the response and merge those data safely into cache. Whenever you write manager.createEntity('Foo'), Breeze uses metadata to construct a new instance of the Foo entity type.

If your application server implements the OData standard, Breeze (usually) can get the metadata it needs with a request to the $metadata endpoint. If your application server relies on the .NET Entity Framework ORM to access the database, Breeze.NET components can generate the Breeze client metadata for you.

Sometimes you’re not that fortunate. Perhaps you can’t touch the server (as illustrated by the “Edmunds Auto Service” sample). Perhaps your server can’t generate the metadata (see the Ruby on Rails and Node/MongoDb samples). You won’t be able to get metadata from the server.

If you’re a .NET developer with access to the server side data model classes, you can use Entity Framework as a metadata generator, as a design-time-only tool, even if you won’t use EF to access data in production. We describe this technique elsewhere.

You don’t have to get the metadata from the server. Breeze metadata on the client is just JavaScript. You can write that JavaScript metadata yourself … as we’ll see here.

We’ll dedicate a JavaScript file to a module that creates a MetadataStore populated with metadata describing the entity types returned by an HTTP service.

Then we’ll create a new EntityManager that uses this metadataStore and show that the manager can create and query entities just fine without requesting metadata from the server.

A Breeze MetadataStore has several parts. The most important is its collection of EntityTypes and creating that collection is the primary focus of this topic.

An EntityType has several important sub-parts that we’ll define by hand:

Breeze has API methods for defining each of these sub-parts separately. We could build up the metadata by calling each method separately. That works … but is more verbose than the approach we’ll demonstrate here.

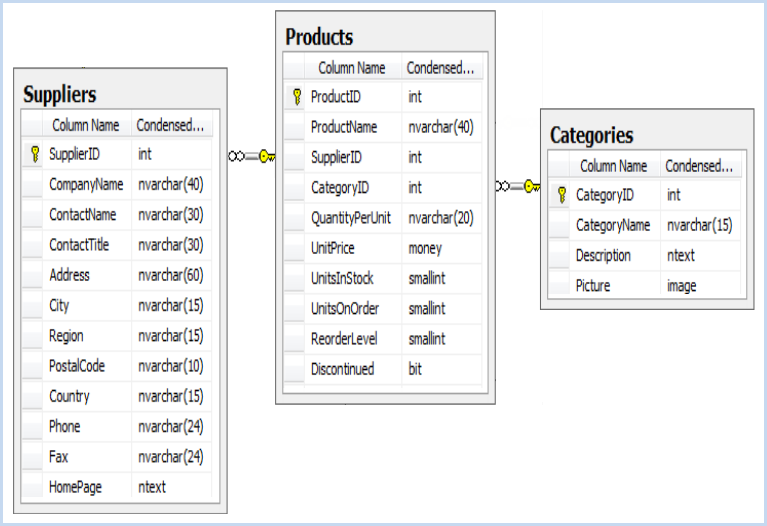

Let’s create a MetadataStore for a three-entity model consisting of Product, Category, and Supplier types. A Product belongs to a Category and has a single Supplier.

The model will map exactly, property-for-column, to three tables of the well-known Northwind database.

Such close correspondence is typical but it isn’t necessary. What matters more is that the client model align with the data structures returned in HTTP response payloads.

The model has a wrinkle. The Supplier address properties (Address, City, Region, PostalCode, and Country) are represented collectively within a single location property that returns a ComplexType. To learn the supplier’s city we’d write supplier.location.city instead of supplier.city.

We’ll need a bit of setup:

// Convenience variables

var DT = breeze.DataType;

var Identity = breeze.AutoGeneratedKeyType.Identity;

var Validator = breeze.Validator;

var camelCaseConvention = breeze.NamingConvention.camelCase;

var serviceName = 'breeze/Northwind'; // root path for data from the server

var defaultNamespace = 'Northwind.Models';

// Breeze Labs: breeze.metadata.helper.js

var helper = new breeze.config.MetadataHelper(defaultNamespace);

var addTypeToStore = helper.addTypeToStore.bind(helper);

This is mostly boilerplate.

We set some variables that make it more convenient to access frequently referenced Breeze objects.

We set two variables with application-specific magic strings (we’ll explain the default namespace below).

We create an instance of the Breeze Labs MetadataHelper class whose functions spare us some cumbersome syntax and much of the error prone repetition that would otherwise mar our metadata writing experience.

The helper saves a lot of time and heartache and is strongly recommended. It is described in detail below.</p>

We’re ready to write the function that creates our handwritten MetadataStore:

// Creates a metadataStore with 3 Northwind EntityTypes:

// Product, Category, Supplier and a Location ComplexType

function createMetadataStore(serviceName) {

var store = new breeze.MetadataStore({

namingConvention: breeze.NamingConvention.camelCase

});

helper.addDataService(store, serviceName);

// Add types in alphabetical order ... because we can

addCategoryType(store);

addLocationComplexType(store);

addProductType(store);

addSupplierType(store);

return store;

}

Now use it to create an EntityManager and execute a query.

var store = createMetadataStore(serviceName);

var manager = new breeze.EntityManager({

serviceName: serviceName,

metadataStore: store

});

breeze.EntityQuery.from("Category")

.using(manager).execute().then(function(data){

alert("Got "+ data.results.length + " 'Category' entities");

});

Let’s dig into the createMetadataStore method.

We must tell our MetadataStore what NamingConvention to use before adding entity types.

var store = new breeze.MetadataStore({

namingConvention: breeze.NamingConvention.camelCase

});

A NamingConvention coverts between the spelling of server property name and the spelling of client property names when serializing and deserializing entity data on the wire.

We configured the new MetadataStore to use the camelCase NamingConvention because we know that the server expects property names to be in PascalCase (e.g., ProductName) while we prefer the camelCase property names that are customary in JavaScript code. We could have written a custom NamingConvention if our server followed some other standard such as the lowercase-underline-heavy convention of Ruby on Rails apps.

Regardless of backend, we specify client-oriented property names in our hand coded metadata, and rely on the NamingConvention to translate to server-side property names.

The Breeze DataService specifies details about the remote server associated with this metadata. It’s most important (and only essential) property is its serviceName which identifies the root path to the remote server.

store.addDataService(

new breeze.DataService({ serviceName: 'breeze/Northwind' }

);

You would add another

DataServiceif you needed this same metadataStore to work with a second remote server at a different address.

And now we’re ready to add the entity types, starting with a simple example

Let’s look at some code and then break it down:

// Definition of a simple reference type

function addCategoryType(store) {

var et = {

// Header info

shortName: "Category",

namespace: defaultNamespace,

autoGeneratedKeyType: Identity,

defaultResourceName: "Categories",

dataProperties: {

categoryID: { dataType: DT.Int32, isPartOfKey: true },

categoryName: { maxLength: 4000 }, // DT.String is the default type

description: { maxLength: 4000 },

picture: { dataType: DT.Binary, maxLength: 4000},

rowVersion: { dataType: DT.Int32, isNullable: false },

}

};

return addTypeToStore(store, et);

}

We’re creating a big configuration object, et (short for “EntityType”), and then passing it to some function that purportedly creates the Category entity type from that config and adds it to the metadataStore (the store). We’ll get to that function in due time.

The config object begins with some “header info”, followed by a list of data properties. Let’s tackle the “header” first.

The shortName is the familiar name of the type, “Category”.

The namespace value identifies the namespace of the “Category” class as it is known on the server-side model, a string such as “Northwind.Models”.

Because we’ll use the same

namespacethroughout our model definition, we’ve captured it in the variablenorthwindNamespace.

The namespace value matters if it matters to the backend; if the backend doesn’t care (e.g. Rails or Node), then it can be anything as long as the client and the server agree on the same value.

In principle we could have two Category types in the metadata as long as they had different namespaces. Accordingly, what uniquely identifies an entity type is its full name - the EntityType.name - which is the shortName + the “:#” separator characters + the namespace. The full name of our Category type is “Category:#Northwind.Models”.

It’s tedious and error prone to have to write the namespace over and over, especially when this model (like most models) only has one namespace. We’ll omit the namespace specification from now on and leave it to the MetadataHelper (helper) to apply the defaultNamespace when the time comes.

How will the system assign a key when we create a new Category entity instance? Should the client assign the key value? Or will the key be assigned on the server (e.g., by the data tier)?

Breeze supports the three choices in the AutoGeneratedKeyType enumeration:

None - the client assigns the key value (default)

Identity - the key properties map to identity columns in a database table; the database generates the key value.

KeyGenerator- the key value is assigned on the server by some form of custom key generation scheme. You’ll have to register a JavaScript key generation function with the EntityManager to maintain temporary keys on the client.

Most entity keys are either client assigned (None - the default) or Identity. All three of our model types have Identity keys.

You can change the default for your model either by specifying it in the helper constructor

var defaultKeyGen = breeze.AutoGeneratedKeyType.Identity;

var helper = new breeze.config.MetaDataHelper(defaultNamespace, defaultKeyGen);

or by setting it explicitly

helper.setDefaultAutoGeneratedKeyType(defaultKeyGen);

The defaultResourceName should be the resource name of the server endpoint that you target most frequently with queries for this type.

The defaultResourceName is typically the plural form of the type name (e.g., “Categories”) because that’s where most people go to “get all” instances of the type.

For example, if I want to get all Category entities, I’ll probably write a Breeze query like this one:

var query = breeze.EntityQuery.from("Categories");

Notice that you can’t tell what type of objects this query returns unless you know that the resource name in the from("Categories") clause is associated with the Category type.

Breeze doesn’t always have to know the query return type. It usually can figure that out from the response data. But sometimes breeze needs to know the type before it can process the query … as it must when executing this query against the local cache.

So give Breeze a hand by specifying a good default resource name. Later will learn how to tell Breeze with metadata about other ResourceName-to-EntityType associations.

Breeze metadata describe two kinds of properties: a Navigation property for getting and setting related entities and a DataProperty for getting and setting other kinds of values.

The Category type doesn’t have navigation properties. Although there is a relationship between Product and Category and you can navigate from a product to its category (Product.category, described below), we opted to omit the navigation property from category to product.

This is an application modeling decision of the kind you’ll make for your own model.

Category does have data properties, each of them an instance of the Breeze DataProperty class. The DataProperty attributes describe many important characteristics of the property such as:

its name in the client model (which differ from its name on the server). [required]

its DataType [defaults to String]

if it is the entity key or part of the key [defaults to false]

if it is required or isNullable [defaults to true]

if its value has a maximum length [optional]

Our Category configuration defines a DataProperties hash object whose keys are the type’s client-side property names and whose values prescribe one or more of those DataProperty attributes.

dataProperties: {

categoryID: { dataType: DT.Int32, isPartOfKey: true },

categoryName: { maxLength: 4000 }, // DT.String is the default DataType

description: { maxLength: 4000 },

picture: { dataType: DT.Binary, maxLength: 4000},

}

You can specify every attribute explicitly or accept the defaults as we have done here.

For brevity we captured the

breeze.DataTypeenumeration in a variable namedDTearlier in the code-base.

A DataProperty also holds a collection of Validators. We could add validators here while we’re defining each property. Instead, we’ll generate some validators a little later in our program.

Check out the DataProperty API docs for the full story on DataProperty attributes.

We’ve completed the configuration object for the Category type. We’re ready to create the type and add it to the MetadataStore … which our code does by calling a helper function

return et = addTypeToStore(store, et)

We’ll delve into that function later in our story. Let’s skip ahead to the definition of the Product type where we’ll learn about navigation properties.

We follow the same course when defining the Product entity type. Here’s a somewhat abbreviated version of the addProductType method.

Later in this topic you’ll learn how to define this type a bit more concisely.

function addProductType(store) {

var et = {

shortName: "Product",

autoGeneratedKeyType: Identity,

defaultResourceName: "Products",

dataProperties: {

productID: { dataType: DT.Int32, isPartOfKey: true },

productName: { maxLength: 40 },

supplierID: { dataType: DT.Int32} ,

categoryID: { dataType: DT.Int32 },

unitPrice: { dataType: DT.Decimal },

unitsInStock: { dataType: DT.Int16 },

discontinued: { dataType: DT.Boolean, isNullable: false },

discontinuedDate:{ dataType: DT.DateTime },

// other properties

},

navigationProperties: {

category: {

entityTypeName: "Category",

associationName: "Product_Category",

foreignKeyNames: ["categoryID"]

},

supplier: {

entityTypeName: "Supplier",

associationName: "Supplier_Products",

foreignKeyNames: ["supplierID"]

},

}

};

return addTypeToStore(store, et);

}

The dataProperties definition illustrates a few of the other DataTypes that Breeze supports.

Our attention turns to a new subject, the navigation properties.

A NavigationProperty describes an entity property that returns a related entity (or collection of entities) from the EntityManager cache.

The Product type has two navigation properties, Product.category and Product.supplier. Here are their definitions again:

navigationProperties: {

category: {

entityTypeName: "Category",

associationName: "Product_Category",

foreignKeyNames: ["categoryID"]

},

supplier: {

entityTypeName: "Supplier",

associationName: "Supplier_Products",

foreignKeyNames: ["supplierID"]

},

}

We’re showing three of the four critical attributes for these navigation properties:

entityTypeName - the name of the type returned by the property

associationName - a name that links this navigation property to a corresponding navigation property on the other side that points back to this object.

foreignKeyNames - the name of the property in this type that holds the foreign key value.

isScalar - whether this navigation returns a single entity object (true) or a collection (false). Because these two properties each return a single entity (or null), we can omit the isScalar attribute and accept the default value (true)

The first three attributes deserve a few more words of explanation.

This required attribute identifies another entity type registered in the metadataStore. We must supply the full type name. For example, we should have written:

entityTypeName: "Category:#Northwind.Models"

We cheated. We’ll get away with it because we’ll later call the addTypeToStore which will patch in the missing namespace for us.

Why cheat? We’ll explain when we discuss that function. Just know (a) that you’ll need to specify the full name and (b) you don’t have to cheat if you don’t want to.

This model has one association between Product and Supplier (“Supplier_Products”) and another association between Product and Category (“Product_Category”).

These names are conventional and somewhat arbitrary. It doesn’t matter which entity type name comes first. In fact, the name itself doesn’t matter at all. You could call it “Association#1” if you like.

The “Supplier_Products” association happens to be bi-directional. There is a Product.supplier navigation and an “inverse” Supplier.products navigation.

The “Product_Category” association happens to be unidirectional. There is only a Product.category navigation; there is no inverse Category.products navigation property.

When an association is bi-directional, Breeze needs to know about both navigation properties. For example, if we assign a product to a supplier, Breeze must update both the product’s supplier property and add this product to the supplier’s products collection. It’s Breeze’s job to keep both sides in-sync.

Breeze knows that two navigation properties are related by association when they have the same associationName. The actual name doesn’t matter. They just have to be the same for both navigation properties.

The foreignKeyNames is an array of property names that identify the foreign key properties in this entity that help Breeze implement the association. Usually there is only one foreign key property and thus only one name in the array.

Breeze asks for an array in anticipation of the possibility that the association requires a compound foreign key.

Breeze needs foreign keys to maintain associations between two related entities. If you set the a cached product’s categoryID to “42”, Breeze looks in cache for a Category with that ID and, if it finds one, it updates the product’s category navigation property accordingly.

The same thing happens when you retrieve a Product from the server. You don’t have to include the related Category in the query response; Breeze fills in the category property automatically. This is what we mean when we say Breeze offers “self-assembling object graphs”.

Your model entities must have foreign keys if you want Breeze perform these services.

We’ve seen two navigation properties leading from Product to two other entity types, Category and Supplier. What about the “inverse” navigations back to Product.

Category doesn’t have one; it could have had a Category.products but we decide to omit it for some reason (perhaps good reasons).

Supplier does have an inverse navigation property, Supplier.products. Its “Supplier_Products” association is bi-directional.

We’ll see how to define that navigation property when we discuss the Supplier type … next.

In the Supplier type we’ll learn how to

ComplexTypeHere’s a slightly abbreviated look at the addSupplierType function:

function addSupplierType(store) {

var et = {

shortName: "Supplier",

autoGeneratedKeyType: Identity,

defaultResourceName: "Suppliers",

custom: {style: "bold", meaningOfLife: 42},

dataProperties: {

supplierID: { dataType: DT.Int32, isPartOfKey: true },

companyName: { maxLength: 40, isNullable: false, custom: {uiHint:"big"} },

location: { complexTypeName: "Location", isNullable: false},

phone: { maxLength: 24 , validators: [ Validator.phone() ] },

// ... other properties

},

navigationProperties: {

products: {

entityTypeName: "Product",

isScalar: false,

associationName: "Supplier_Products"

}

}

};

return addTypeToStore(store, et);

}

The Supplier.products property is the inverse of the Product.supplier navigation on the Product type. It’s the flip side of the “Supplier_Products” association and we know that because both navigation properties share the same associationName.

It differs from Product.supplier in two ways.

This direction is one-to-many; a Supplier has many products. The products property returns a collection of Product entities. Therefore, we set the isScalar attribute to false.

We don’t need to identify the foreign keys supporting the association.

The latter point bears explaining.

Breeze associations must be supported by foreign keys if Breeze is to do the work of maintaining the navigation properties as we explained above.

One of the association navigation properties must identify the foreign keys. The Product.supplier property took care of that already. We don’t have to repeat that information in the Supplier.products property.

We would have to code this navigation property a little differently if there were no

Product.supplierproperty; see below for details.

The MetadataStore holds a lot of useful information about each entity type in the model and that information is pretty easy to access at runtime. First you fish out the type of interest.

var type = manager.metadataStore.getEntityType('Category);

Then you drill into its properties until you find what you want.

Wouldn’t it be grand if you could supplement the Breeze metadata with your own metadata? Then there would be a single place to find everything about a type.

Technically, this being JavaScript, you can extend any object by simply assigning a property to it. No one can stop you from tacking an arbitrary object onto a MetadataStore.

Please don’t do that. You’ll miss out on Breeze’s ability to export and import metadata … because Breeze only exports metadata properties that it recognizes.

Fortunately, Breeze recognizes a metadata attribute called custom and you can assign it with anything you want … as long as that thing can be JSON.stringified for export/import.

Suppose we are fans of “Model Driven Architecture” and we intend to generate portions of the UI based on metadata associated with our model object properties. We might have “UI Hints” that tell the UI builder to display instances of certain types in bold colors. Maybe the “companyName” should appear in a large font.

We could store these hints in a private application registry. But it’s so much easier and more obvious to stash them in custom attributes of the MetadataStore.

The Supplier sample demonstrates two forms of custom metadata. There’s custom information at the the entity level:

custom: {style: "bold", meaningOfLife: 42}\

and custom information at the property level in Supplier.companyName:

companyName: { ... custom: {uiHint:"big"} },

Breeze itself ignores custom metadata attributes except when importing or exporting a ‘MmetadataStore`. What you do with them is up to you. You can add or remove them any time. Breeze will include custom attributes when (and if) it serializes metadata.

The “Supplier” table has several columns that collectively describe the shipper’s address.

We mapped those columns to the properties of a higher level construct called Location which is implemented as a ComplexType as we see in this extract of the data properties section.

location: { complexTypeName: "Location:#Northwind.Models", isNullable: false},

/* if we didn't have Location ComplexType

address: { maxLength: 60 },

city: { maxLength: 15 },

region: { maxLength: 15 },

postalCode: { maxLength: 10 },

country: { maxLength: 15 },

*/

Now we can access the city property through the Location. Instead of writing someSuppler.city we can write someSupplier.location.city.

Of course we must also add the Location definition to the metadata. Here we’ve written an addLocationComplexTypemethod for that purpose..

function addLocationComplexType(store) {

var et = {

shortName: "Location",

isComplexType: true,

dataProperties: {

address: { maxLength: 60 },

city: { maxLength: 15 },

region: { maxLength: 15 },

postalCode: { maxLength: 10 },

country: { maxLength: 15 },

}

};

return et = addTypeToStore(store, et);

}

Writing a special ComplexType class and then replacing properties with this new type … seems like a lot of work. It doesn’t seem worth doing just once. It might payoff if we could re-use the Location type elsewhere in the model.

As it happens, the Northwind database has four tables (“Customer”, “Employee”, “Order”, “Supplier”) that have the same location properties. The four corresponding entity types are all candidates for the Location complex type treatment.

We typically add Validators after the types have been registered. But you also can add Validators to a property definition while defining that property. The Supplier.phone is an example:

dataProperties: {

...

// example of embedding a validator in the metadata

phone: { maxLength: 24 , validators: [ breeze.Validator.phone() ] },

...

}

Notice that the data property has a validators array whose elements are instances of the Validator class.

We’ll use addTypeToStore to complete the process of defining metadata for our model.

The

addTypeToStoremethod and related helper functions are not part of core Breeze. They belong to the Breeze LabsMetadataHelperextension defined in breeze.metadata-helper.js. Download it from GitHub and install it on your page after loading breeze.

So far we’ve created object hashes that describe three entity types - Category, Product, and Supplier - and one complex type, Location. Let’s turn those hashes into Breeze types and add them to the MetadataStore using the addTypeToStore helper.

Create an instance of the helper at the top of your metadata creation script as we did

var defaultNamespace = 'Northwind.Models';

...

var helper = new breeze.config.MetadataHelper(defaultNamespace);

var addTypeToStore = helper.addTypeToStore.bind(helper);

addTypeToStoreis only one way to achieve an efficient metadata writing workflow by conventions. That way may not suit your model or your preferred style. Please use as inspiration, not prescription.

With that caveat in mind, we’ll continue describing the addTypeToStore and its supporting methods in the Breeze Labs breeze.metadata-helper.js script.

// Create the type from the definition hash and add the type to the store

// fixes some defaults, infers certain validators,

// add adds the type's "shortname" as a resource name

function addTypeToStore(store, typeDef) {

patchDefaults(typeDef);

var type = typeDef.isComplexType ?

new breeze.ComplexType(typeDef) :

new breeze.EntityType(typeDef);

store.addEntityType(type);

inferValidators(type);

addTypeNameAsResource(type);

return type;

}

There are five steps:

Tweak the type definition hash with some defaults that Breeze doesn’t know about.

Create a type instance from the definition hash, either a ComplexType or an EntityType. We mostly create EntityTypes although we did create one ComplexType, Location, and used it within Supplier.

Add the type to the store with the Breeze MetadataStore.addEntityType method. Once you’ve done this, the type definition is “frozen” in many respects. You can’t add more mapped properties, you can’t add the same type again, and you can’t remove a type once it’s been added. Choose this moment wisely.

Infer some validators for each data property based on the property’s data type and its nullability.

Tell breeze that the entity’s own name is a valid “resource name” for local queries.

We strive to minimize the amount of configuration code. Magic strings in hash objects are a necessary evil; anything we can do to reduce repetition and infer values improves readability and maintainability. So in our configurations above we’ve abbreviated or omitted some values that Breeze ultimately requires, trusting that we’ll be able to fill the gaps later.

For example, Breeze requires all type names to include the namespace. Most models only have one namespace. In this code, you can omit the namespace and let patchDefault supply it later.

The time for “later” is now. The patchDefault method sweeps the configuration object, making eight fixes:

ComplexType property’s type name lacks a namespace, add the entity’s namespace. Ex: “Location” becomes “Location:#Northwind.Model”.isNullable=false unless told otherwise.breeze.Validator instance.Product.category navigation.Here is patchDefaults almost in its entirety:

function patchDefaults(typeDef) {

var key, prop;

...

var typeName = typeDef.shortName;

// if no namespace specified, assign the helper defaultNamespace

var namespace = typeDef.namespace = typeDef.namespace || this.defaultNamespace;

if (!typeDef.isComplexType) {

// if regular entityType lacks an autoGeneratedKeyType, use the helper defaultAutoGeneratedKeyType

typeDef.autoGeneratedKeyType = typeDef.autoGeneratedKeyType || this.defaultAutoGeneratedKeyType;

}

var dps = typeDef.dataProperties;

for (key in dps) {

if (_hasOwnProperty(dps, key)) {

prop = dps[key];

this.replaceDataPropertyAbbreviations(prop);

if (prop.complexTypeName && prop.complexTypeName.indexOf(":#") === -1) {

// if complexTypeName is unqualified, suffix with the entity's own namespace

prop.complexTypeName += ':#' + namespace;

}

// if key is named 'id' and isPartOfKey is null or undefined, infer isPartOfKey

if (key.toLowerCase() === 'id' && prop.isPartOfKey == null) {

prop.isPartOfKey = true;

}

// assume key part is non-nullable ... unless explicitly declared nullable (when is that good?)

prop.isNullable = prop.isNullable == null ? !prop.isPartOfKey : !!prop.isNullable;

if (prop.validators) { this.convertValidators(typeName, key, prop); }

}

};

var navs = typeDef.navigationProperties;

for (key in navs) {

if (_hasOwnProperty(navs, key)) {

prop = navs[key];

this.replaceNavPropertyAbbreviations(prop);

if (prop.entityTypeName.indexOf(":#") === -1) {

// if name is unqualified, suffix with the entity's own namespace

prop.entityTypeName += ':#' + namespace;

}

// coerce ...keyNames to array

var keyNames = prop.foreignKeyNames;

if (keyNames && !_isArray(keyNames)) {

prop.foreignKeyNames = [keyNames];

}

keyNames = prop.invForeignKeyNames;

if (keyNames && !_isArray(keyNames)) {

prop.invForeignKeyNames = [keyNames];

}

}

};

}

Some of the metadata attributes are a bit long winded. Fortunately, you often can abbreviate the more common attributes and patchDefaults will translate to the offical Breeze attribute names.

Here are some examples:

Use name instead of shortName for an EntityType

type becomes dataTypenull become isNullablemax on a string property becomes maxLengthkey become isPartOfKeydefault becomes defaultValuetype becomes entityTypeNameFK or FKs becomes foreignKeyNamesinvFK or invFKs becomes invForeignKeyNamesassoc becomes associationNameThe validators attribute should be assigned an array of validators. It’s easy to forget the array brackets when you only have one validator. patchDefault will coerce that into a one-element array for you.

The foreignKeyNames and invForeignKeyNames attributes should be assigned an array of foreign key property names. In practice, navigation properties are almost always backed by exactly one FK property. If you omit the array brackets, patchDefault will coerce the string value for the FK property name into a one-element string array for you.

Here’s how abbreviations and array coercion might simplify the Product type definition we saw earlier.

function addProductType(store) {

var et = {

name: "Product",

defaultResourceName: "Products",

autoGeneratedKeyType: Identity,

dataProperties: {

productID: { type: DT.Int32, key: true },

productName: { max: 40 },

supplierID: { type: DT.Int32} ,

categoryID: { type: DT.Int32 },

unitPrice: { type: DT.Decimal },

unitsInStock: { type: DT.Int16 },

discontinued: { type: DT.Boolean, nullOk: false },

discontinuedDate:{ type: DT.DateTime },

// other properties

},

navigationProperties: {

category: {

type: "Category",

assoc: "Product_Category",

fk: "categoryID"

},

supplier: {

type: "Supplier",

assoc: "Supplier_Products",

fk: "supplierID"

},

}

};

return addTypeToStore(store, et);

}

A property that is not nullable is probably required. The property should have a required validator. When we set a property value and the property has a data type, we probably want to confirm that the value matches the data type. The property should have the appropriate data type validator.

If we specified a maxLength for a string property, the property should carry the maxLength validator.

The developer shouldn’t have to specify these validators when we can infer them so easily. The inferValidators method takes carry of this.

Breeze infers these validators automatically when it processes metadata received from the server. We’re writing metadata by hand on the client so we have to do it ourselves.

function inferValidators(entityType) {

entityType.dataProperties.forEach(function (prop) {

if (!prop.isNullable) { // is required.

addValidator(prop, Validator.required());

};

addValidator(prop, getDataTypeValidator(prop));

if (prop.maxLength != null && prop.dataType === DT.String) {

addValidator(prop, Validator.maxLength({ maxLength: prop.maxLength }));

}

});

return entityType;

function addValidator(prop, validator) {

if (!validator) { return; } // no validator arg

var valName = validator.name;

var validators = prop.validators;

var found = validators.filter(function (val) { return val.name == valName; })

if (!found.length) { // this validator has not already been specified

validators.push(validator);

}

}

function getDataTypeValidator(prop) {

var dataType = prop.dataType;

var validatorCtor = !dataType || dataType === DT.String ? null : dataType.validatorCtor;

return validatorCtor ? validatorCtor() : null;

}

}

The getDataTypeValidator is noteworthy in two respects.

Breeze’sdataType.validatorCtor property tells us what Validator to use.

We can’t use the data type Validator for a string property because we lack the length information that Validator.string() requires.

We often write Breeze queries that apply to the local cache. For example,

var query = breeze.EntityQuery.from('Product')

.where('categoryID', '==', someCategoryId);

// query the cache synchronously

var categoryProducts = manager.executeQueryLocally(query);

Notice that this particular query addresses a resource named “Product”. That seems natural and you might think that an EntityType name is always a valid resource name.

It is not! At least it is not by default. Resource names are typically server-side controller method names. This application has a Web API controller that exposes a “Products” (plural) endpoint; it doesn’t have a “Product” (singular) endpoint. Accordingly, the Product default resource name is “Products”, not “Product”.

Fortunately, we can associate the Product type with additional resources names … such as the EntityType name. That’s the point of the addTypeNameAsResource method:

// Adds the type's 'shortName' as one of the resource names for the type.

function addTypeNameAsResource(store, type) {

if (!type.isComplexType) { // don't do this for ComplexTypes

store.setEntityTypeForResourceName(type.shortName, type);

}

}

Note how this method excludes ComplexType names. A ComplexType is not an entity and is not directly queryable in the cache.

While we can associate an EntityType with as many resources names as we wish, we must make sure that a given resource name is associated with exactly one type! There is a remote possibility that our model has two types with the same short name but different namespaces. The way we call this method in addTypeToStore, we would unintentionally associate the same resource name with the two different types. We could fix that later by removing one or both of these “shortName” resources and optionally adding fullname resources.

In this section we talk about some corner cases.

Although the elements of a data property’s validators array must be instances of the Validator class Breeze knows how to turn a JSON string representation of the validator into a breeze.Validator object.

We harnessed that trick in a helper function called within the patchDefaults helper:

function convertValidators(typeName, propName, propDef) {

...

propDef.validators.forEach(function (val, ix) {

...

try {

validators[ix]=breeze.Validator.fromJSON(val);

} catch (ex) {

...

}

});

}

The pertinent expression in there is

breeze.Validator.fromJSON(val); // val is in JSON format

Using this technique, we could have written the Supplier.phone property definition as

phone: { maxLength: 24, validators: [ {name: 'phone'} ] },

This convertValidators helper also coerces a single validator into a one-element array of validators as Breeze requires.

We usually have navigation properties on both sides of an association. The “Supplier_Products” association, for example, is represented by both a Suppler.products and a Product.supplier navigation property.

Breeze needs foreign keys in order to maintain an association for reasons we explained above. One of the navigation properties must identify the foreign key properties that support the association.

Identifying the foreign keys is usually the job of the navigation property on the “dependent” type. Which end of the association is the “dependent type”? Looking again at “Supplier_Products” we see that

The Supplier type is the “principal” in this association; we know that because it doesn’t possess foreign key properties that point to Product.

The Product type is the “dependent” entity in this association because it does hold the foreign key properties that point to Supplier.

By custom the Product.supplier property should identify the foreign key properties … as it does with the navigation attribute:

foreignKeyNames: ["supplierID"]

Now we don’t have to define both navigation properties. We can omit a navigation property that we don’t need or want. When there is only one navigation property we say that the association is “unidirectional”.

That means the lone remaining navigation property must fulfill the requirement of identifying the pertinent foreign keys.

We could remove the Supplier.products property and keep the Product.supplier navigation. Product.supplier already identifies the foreign key properties so we don’t have to do anything else.

We could ditch the

associationNameas well; it’s only required to associate bi-directional navigation properties. However, we prefer to retain theassociationNamefor future proofing.

Imagine instead that we want to keep the Supplier.products property and remove the Product.supplier navigation. In so doing, we’d be removing the foreignKeyNames attribute that identifies the foreign keys.

Somebody has to identify the foreign keys. The Supplier.products property will have to do it.

Unfortunately, we can’t put the foreignKeyNames attribute on the Supplier.products property. Supplier is the “principal” entity in the association and it doesn’t possess the association foreign key properties. The foreign key properties are physically on the “dependent” Product entity. So we apply the invForeignKeyNames attribute instead to make this difference clear.

invForeignKeyNames: ["supplierID"]

The “inv” prefix tells Breeze to look for the foreign keys on the other entity, the “inverse” Product entity.